LOCAL

LEAD ARTIST: JOHAN THURFJELL (SE)

ARTISTS: JULIA ADZUKI (SE) LINDA SHEVLIN (IE) BRIGITTA VARADI (IE) KAROLINA ŻYNIEWICZ (PL)

For Locis 2014, the Irish residency was led by Swedish artist Johan Thurfjell, with participating artists Linda Shevlin, Brigitta Varadi, Karolina Żyniewicz and Julia Adzuki. The group convened for three separate stays in Leitrim – an unknown landscape for three of the artists, but familiar to the other two who reside here. Leitrim-based arts writer and researcher Joanne Laws met the group during their visit in September 2014, to gain an insight into the various projects that were underway at the time, and to probe the thematic inquiries emerging from the residency process. Joanne Laws: Johan, as lead artist, can you describe some of your original ideas for the 2014 Irish residency, with regard to the Leitrim setting?

Johan Thurfjell: The only thing I knew about Carrick-on-Shannon, when I was invited to lead the residency, was that it was beautiful, small and rural. I devised a very straightforward idea for the artists in the group to just spend time together in Carrick, and to work intuitively with the location as our thematic starting-point. I myself experienced moving from an urban setting (Stockholm) to a rural village in the country side, and continue to reflect on how this relocation has affected my studio practice. Based on this experience, I was certain that I wanted all of us to make new work for the upcoming exhibition, which would concentrate our sessions together and focus the individuality of our shared experience.

Johan Thurfjell: The only thing I knew about Carrick-on-Shannon, when I was invited to lead the residency, was that it was beautiful, small and rural. I devised a very straightforward idea for the artists in the group to just spend time together in Carrick, and to work intuitively with the location as our thematic starting-point. I myself experienced moving from an urban setting (Stockholm) to a rural village in the country side, and continue to reflect on how this relocation has affected my studio practice. Based on this experience, I was certain that I wanted all of us to make new work for the upcoming exhibition, which would concentrate our sessions together and focus the individuality of our shared experience.

JL: How have these unfolding experiences of the rural Irish landscape informed your own artistic inquiry?

JT: I find the Irish mythology more present and visible in the landscape than in the Swedish. Since I’m interested in mythologies in general, and mythological creatures in particular, I wanted to further explore Irish mythology upon my arrival. When the group met for the first time, we embarked on some extensive sightseeing to places of interest. In Sligo, we met wood-carver Michael Quirke, who introduced me to the myth of the Dobar Cù – the ‘dark wet hound’. This myth states that all of us, at some stage in our lives, will eventually need to visit the ‘Underworld’. Down there, within ourselves, this monster lives, and to pass him we must become friends with him. This myth became the door-opener back into a project I’ve been working on at home for some time. In my piece for the exhibition I am using the Dobar Cù myth as a framework for a story based on own personal experiences of life.

JL: Some of you have been working with the natural elements and materials of the west of Ireland. Has this process revealed unexpected connections with your own native landscapes?

Julia Adzuki: The experiences of the residency in Ireland have provided a strong reminder of my Celtic family origins and some insights into underlying mythologies. Growing up in Australia, my childhood was rich in direct experience with wilderness and rural landscape, informing much of my work with natural and ephemeral materials. Through ritual actions with poetic instruments I am attempting to document something of the reciprocal exchange between landscape and body. Mythology, I have come to realise, provides a lens through which the reciprocal interaction of nature and human are acknowledged, in contrast to the prevalent and observable scientific perspective. Exploring megalithic tombs, holy wells and fairy forts awoke an awareness of the many layers of earth meeting the feet with each step. My fascination with the Sheela Na Gig, lead to creating vulva mask forms of Kombucha (bacterial culture of fermented tea) symbolising the Mother and passage of life from which we emerge and eventually return.

Julia Adzuki: The experiences of the residency in Ireland have provided a strong reminder of my Celtic family origins and some insights into underlying mythologies. Growing up in Australia, my childhood was rich in direct experience with wilderness and rural landscape, informing much of my work with natural and ephemeral materials. Through ritual actions with poetic instruments I am attempting to document something of the reciprocal exchange between landscape and body. Mythology, I have come to realise, provides a lens through which the reciprocal interaction of nature and human are acknowledged, in contrast to the prevalent and observable scientific perspective. Exploring megalithic tombs, holy wells and fairy forts awoke an awareness of the many layers of earth meeting the feet with each step. My fascination with the Sheela Na Gig, lead to creating vulva mask forms of Kombucha (bacterial culture of fermented tea) symbolising the Mother and passage of life from which we emerge and eventually return.

Karolina: Like Julia, nature is also my main source of my inspiration, so Ireland’s influence was very intense. It seems almost impossible to imagine responding to this place without incorporating nature, which determines all aspects of life here, more or less directly. Death is a special moment of human return to nature, ancestors and the earth. Because I am fascinated with funeral traditions, everywhere I travel I visit cemeteries, searching for information about cultural rites.

Karolina: Like Julia, nature is also my main source of my inspiration, so Ireland’s influence was very intense. It seems almost impossible to imagine responding to this place without incorporating nature, which determines all aspects of life here, more or less directly. Death is a special moment of human return to nature, ancestors and the earth. Because I am fascinated with funeral traditions, everywhere I travel I visit cemeteries, searching for information about cultural rites.

Peat is a natural treasure of Ireland, which is inscribed in tradition, through its multiple uses as a fuel, fertilizer, medicine, and cosmetic. Comprised from dead matter such as plant debris, peat is also a natural preservant, demonstrated by the human remains which have been naturally mummified within peat bogs, presenting these bogs as ‘natural cemeteries’. The work I have developed during the LOCIS residency has been informed by Polish and Irish funeral traditions. It has involved the construction of ‘Peat Cemeteries’ – simple tombs made from peat briquettes– and ‘Pantry/Cemetery’ experiments, involving the preservation of various foodstuffs in peat.

As the youngest member of the Irish residency group, I learned a lot from the other artists. Julia taught me how to make kombucha, and Brigitta taught me how to spin wool. We shared many significant things from our art practices, as well as personal life experiences.

JL: Brigitta, although you moved to Ireland in the nineties, you have articulated your sense of being ‘neither native nor foreigner’ in the context of the LOCIS residency. Has the visiting artists’ responses to the west of Ireland (re)famed your connections with Ireland and/or your native Hungary?

Brigitta: The residency created a platform for dialogue on so many levels, and brought to the surface several questions that have been brewing, regarding how I (re)examine my own identity, especially since spending more and more time in New York. Almost like a travelling monk, I journey between three different places in the world, observing significant differences which might not have been invisible had I only stayed in one location. The residency journey has become a vehicle for reconnecting my past, present and future, with the aim of finding a place of contentment embedded in three different cultures. Through the mix of cultural origins of the other LOCIS artists, and their interest in the landscapes and mythologies of the west of Ireland, I have begun to reconnect with my Hungarian cultural heritage and my deep enduring love affair with Ireland.

JL: Linda, as the only Irish person on this year’s Leitrim residency, have the visiting artists’ impressions of Ireland (re)framed your perceptions of your local landscape?

Linda Shevlin: Rationalising my relationship to my immediate environment – both physically and socio-historically – is an ongoing concern within my work, but it has certainly been heightened through this residency process. What appealed to me in Johan’s initial proposal was the capacity to play out associations between physical relationships to ‘place’ and culturally constructed notions of identity, and I was curious to see where that might lead.

Linda Shevlin: Rationalising my relationship to my immediate environment – both physically and socio-historically – is an ongoing concern within my work, but it has certainly been heightened through this residency process. What appealed to me in Johan’s initial proposal was the capacity to play out associations between physical relationships to ‘place’ and culturally constructed notions of identity, and I was curious to see where that might lead.

JL: How has this trajectory influenced your current work?

LS: Although the thematic structure of my work can vary, the underlying conceptual inquiries tend to be site-responsive, often located in proximity to my home (e.g. Lough Key Forest Park, The Moylurg Tower, the ballrooms of Roscommon and The Organic Centre in Rossinver etc..). The LOCIS process, and the time spent with the group visiting the ‘mythologically-loaded’ sites I have previously overlooked, has allowed me to connect several abstract concepts in my work: The occult, mythology, magic and science fiction, paradigm shifts from historical fact to fiction, and the representation of these things in modern science and popular culture.

JL: Any branch of mythology in particular?

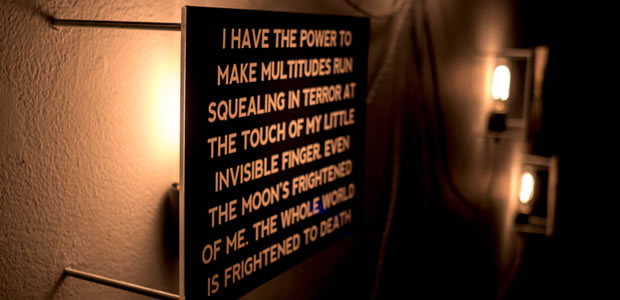

LS: I’m looking at the origins of writings on mythologies, such as ‘The Book of Invasions’– an account of Irish history as recorded by medieval scholars. It contains pre-Christian elements and was considered an accurate account of Irish History until relatively recently. Mostly considered myth now, it has been argued that it was based loosely on actual events. Mythological tropes such as the ‘invisibility cloaks’ worn in battle, denote a power that has subsequently been explored in popular culture, from the Brothers Grimm stories and ‘The Invisible Man’, to Samuel R. Delany’s ‘Dhalgre’ – a book closely linked to Greek and Roman mythology.

JL: Johan, perhaps you could offer some concluding thoughts. How are you reflecting (at this mid-way point) on the artists’ responses to your brief, and the projects they have embarked on so far?

JT: The group is responding to my proposal just as I had hoped it would. The five of us have dug ourselves into new projects, finding our own different ways of responding to the geographic location. Since the Irish mythology is so present in the landscape, we have all naturally gravitated towards the subjects of mystique, ritual and myth. Our individual experiences of the residency differ slightly: For me, Julia and Karolina – the foreigners in the group – Ireland is untouched territory, offering perhaps a ‘push into practice’ resulting from excitement of the new. Brigitta and Linda have a different challenge. They live here, and already have a long history of working with the locality in their practice. Our differing positions and approaches to the subject matter have been important for the dynamic within the group. Throughout our three working sessions in Carrick, we have come close to each other on a personal level and also through our practice, allowing us to help and support each other with the challenges of our projects, which is a situation that I find ideal. Photos on porcelain are an integral part of my installation Postnecropolis, making for the exhibition in The Dock Arts Centre. It is a special combination of Polish and Irish funeral traditions tied also with a concept of posthumanism. The photo portraits of people, which in Poland are placed on the graves, are in my work devoted to the plants growing and dying on the peat bog. It could be understand as a story about circle of matter.

Johan Thurfjell’s work spans a great variety of media; from painting to video, sculpture, model making, photography and text. Often the visual language interacts with a subtext to make a more complex structure, which like a camouflage pattern can only be read after a while. This structure of telling generates the kind of dynamic that constitutes the force -field of the work. Johan himself says that he sees his work as metaphors, like ‘“cubes of condensed bouillon where stories have been reined in and cooked down’”. It is often a question of fragments taken fromof the artist’s memories combined with elements taken out of context that form this world of fiction. Something that reflects and accentuates the effect ofthe imagination on life, the wear of time on memory, and the influence of fiction on reality. Johan currently lives in the countryside one hour south of Stockholm.

My practice is informed by reciprocal relationships within nature, the exchange of the body and surroundings, and the return of ephemeral mediums such as ice and snow. It was the ice that first drew me north, from Tasmania to Lapland. I had begun playing with temporal ice installations, filling latex moulds in the freezer at home. I was captivated and longing longed to meet wild ice, ice as expansive space, void and habitat. For seven7 winters I lived far north, exploring these materials, watching creations trickle back, returninged to the melting river each spring.

Unwittingly, Sweden had become my home. Another seven years on, I am exploring the reciprocal exchange of the body and surroundings through kinaesthetic experience, movement in the landscape and poetic actions documented as film. The key tools in my process now are the Skinner Releasing Technique – a somatic dance practice and the Tarot of Marseille. Both provide a lens through which the reciprocal interaction of nature and humans are experienced// symbolised. The kinaesthetic experience of reciprocity with our environment has the capacity to heal fractures between ourselves and the Other – the Nature we have stepped outside of in our minds, that is so essentially us. From each breath to the wind, the water circulating in our bodies passes on its waypasses through countless fluid beings.

Linda Shevlin is a visual artist and curator based in Co. Roscommon, Ireland. Her projects unpack the complexities of modernity’s effects on land and the socio-cultural landscape of her environment. Her recent work has drawn attention to the role that certain historical/ mythological tropes and characteristics have played in inspiring recent scientific research and how these ongoing inquiries have infiltrated popular culture. Using exhibitions, film, and installations she creates situations that explore the borders of fact, fiction and reality.

My work explores how memories can inform our present day perspectives and artistic expression. I like to find beauty, rhythm and patterns around me in a search to find the hidden, invisible element that which gives us simple pleasure in our everyday life. I am also interested in the aesthetics of these patterns and its slowly built constructions. Using different types of fibres and techniques I search for reflection, a momentary flash of emotion, for a surface that contains many meanings and memories. The process of the technique I use, felt making, reflects the essence of my work, an erosion of memories through repetitive action till all that remains is the action itself.

The work I developed during my residency becaome a vehicle for reconnecting my past, present and future, with the aim of finding a place of contentment embedded in three different cultures, Hungary, Ireland and USA and unifying the fragments of my daily life, reflecting its essence of renewal and memories of the past.

At the core of my interest lies the balance between nature and culture, as I see them represented through visual arts. Nature provides me with the set where I can examine the field of aesthetics. At some point in my creative practice, I came to the conclusion that representational work was no longer satisfying.

Why imitate something when you can interact with it? Art, in my mind, should be a kind of investigation, similar to that of science. The most important aspect is the process. The art piece or exhibition is only “alive” for a certain time, like all living beings. For me, it is about asking questions, researching, and the adventure. A great part of my work comes out of curiosity. I am interested in all aspects of the natural world but I can’t access all of it. Art gives me the possibility to use every area of knowledge without specialisation. It is a place where I can make relationships between different layers of thinking. For some time I have been developing concepts of post-humanism in my work, which could be understood as the equality of all living beings. My recent projects connected to this are Postnecropolis and Taste of borders.